Brain Break Strategies for the Classroom

Brain Break Strategies for the Classroom

Teachers learn quickly that it’s best to have an activity or game in their back pocket for those spare five minutes between lessons or as a means of shamelessly bargaining with students for ten more minutes of focus. But as more and more research into the benefits of brain breaks emerges, these ‘games’ have begun to be viewed in a different light. So what are brain breaks?

Brain breaks are short, planned activities within lessons that allow the restoration of neurotransmitters and the engagement of different regions in the brain. When students struggle to concentrate, become bored, or are disruptive, brain breaks can allow students to refocus, continue learning, and retain this learning.

As every teacher will know, the beginning of lessons are often the most productive where students are fully engaged and more likely to retain new information or skills. However, as the lesson progresses this focus can begin to decline. Students suddenly need the restroom more frequently or pencils that need sharpening unexpectedly emerge. There will be students who silently zone out becoming statuesque while others will have the sudden urge to regale you with their cheese sandwich from lunch. Whatever the reason, the one thing you know for sure is that the lesson has most definitely come to an end.

As a new teacher, my first instinct was often to plow on, come what may, even though those dreaded double-period blocks with no end in sight. With a curriculum already feeling impossible to cover, who had time for brain breaks!

With experience came the understanding that pushing through when students were evidently no longer engaged was essentially a waste of time and frustrating for both students and myself. Brain breaks are now an essential strategy that I employ whenever needed that have significantly improved student engagement and learning.

Brain Break Strategies

- Sooner rather than later

I have found it far more effective to employ brain breaks preemptively rather than waiting too long and watching the classroom descend into chaos. How long into the lesson before you use a brain break will depend on the age of the students and the task. Lessons that require greater focus than usual or where students are sitting still working independently may require a brain break sooner compared to other lessons. - Know your students

When creating your repertoire of brain break activities, knowing your students is key. For example, I would have had greater success sprouting pink polka dot wings than getting my previous Grade 5 students to dance. They were however an athletic bunch so plank challenges and paired stretching activities were far more effective! If your class is overly excitable then certain games may be too stimulating, making it harder to get students back on task. Having a good understanding of your class’s strengths and likes will make the use of brain breaks more effective and time-efficient.

- How long should brain breaks last?

The length of a brain break will depend on your students and their needs. Start with five to ten minutes and then adjust based on how your students respond and how much time you have within the lesson. When brain breaks are first introduced they can often take longer than expected as students will be learning a new routine and how to transition between brain breaks and the lesson. However, I have found these transitions become more efficient with practice with students also gaining more independence.

- Introducing brain breaks for the first time

I have found that explaining the purpose of brain breaks to students and discussing how they can be helpful in terms of their learning to be an important step. It is also best to introduce one activity at a time and ensure that students understand how it should be run before introducing a new one. Setting clear boundaries and practicing how to transition to the activity and back to the task will be time well spent and something your future self will thank you for!

- Self-regulation

Brain breaks can range from independent activities to whole-class games. Once a set of independent and small group activities have been introduced, students can begin to self-regulate themselves and learn to recognize when they need a break. While the aim is not for students to give themselves an hour-long juice box break, you do want them to begin recognizing when they need a break and be able to manage this themselves. Setting parameters around how many brain breaks they can take, which ones they can use and how to use timers can be helpful. Again, this will take additional time to set up but is well worth the effort!

Brain Break Ideas

There are a variety of brain break activities that can be used to suit the needs of your students and the time available. Physical movement, changing the type of mental activity, or simply moving to another part of the room can all serve as effective brain breaks.

Independent Brain Breaks

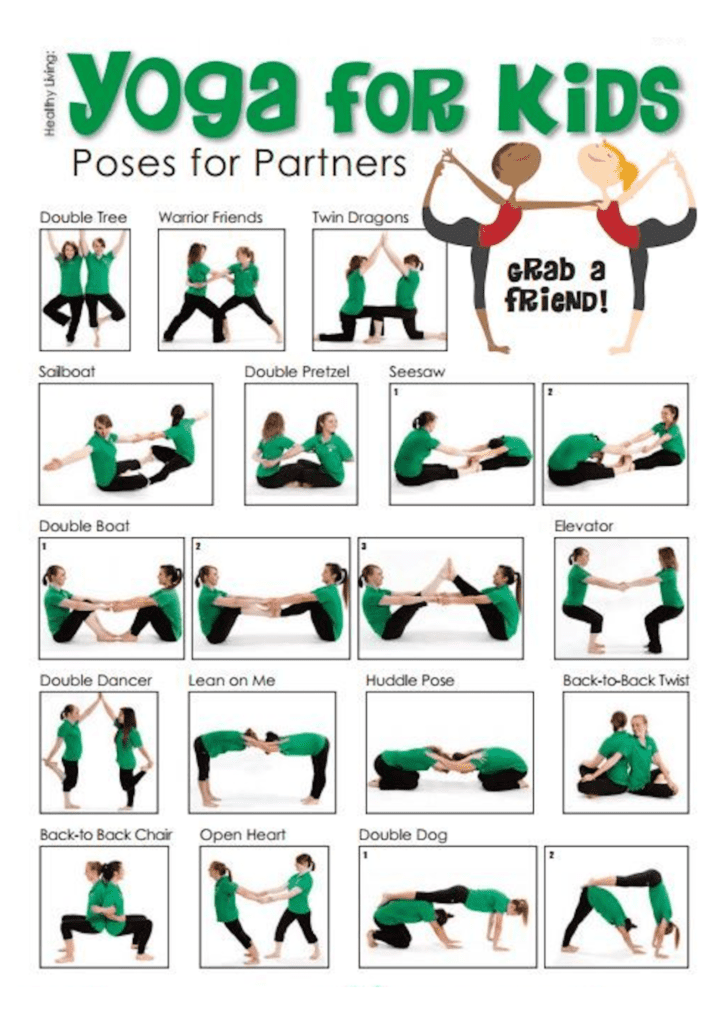

- Stretching or Yoga poses

Have some display sized cards of yoga moves or stretches that students can access and complete themselves

- Mindful coloring

Having a mindful coloring pack that students can go to is a quick and easy activity to re-center students

- Reading

Reading is another quick and calming activity and doing so in a different part of the room can be even more effective

- Handwriting or touch-typing practice

Websites such as Typing.com can be used to practice touch typing if students have access to a laptop or iPad with a keyboard

Whole Class or Small Group Brain Breaks

- Wink, Wink, Sleep

Everyone stands in a circle. Choose one student to be the detective and wait outside. Select another student to be the one who puts the others to ‘sleep’. This student will wink at the others without the detective seeing. Invite the detective back in and ask them to stand in the middle of the circle. The student selected to put the others to sleep will discreetly wink at them one by one. When a student is winked at, they must fall to the ground and pretend to be asleep. The objective is to put as many children to sleep as possible before the detective works who is doing the winking! This is a quick and fun game that works well for older and younger students.

- Rhythm Maker

Begin by asking the students to sit in a circle. One student is chosen to be the detective and is sent outside while another student is chosen to be the rhythm maker. Their job is to create a rhythm by clapping their hands and tapping their knees. As this student changes the rhythm or pattern the other students must copy this. The detective then comes back into the room and must work out who the rhythm maker is!

- Silent Ball

You will need a medium-sized softball such as a foam ball or beach ball. Ask the students to spread out in the available space. The player selected to start passes the ball to another student. Students are out and must sit down if they;

– Drop the ball

– They talk or make a sound

– They make a bad throw

– Pass the ball back and forth between the same 2 or 3 players

– Take longer than 3 seconds to throw (This time can be increased for younger players)

Continue until one player remains standing. There are many variations to this game such as decreasing the passing time, banning overhead throws, using a smaller ball, and having one hand behind their backs. This is a great brain break activity as it is quick, requires few resources, and includes physical movement, change of mental activity, and change of location.

- Silent Line Up!

Ask students to line up silently based on different criteria;

– Line up from youngest to oldest

– Line up by height

– Line up by hair length

– Line by alphabetically - Dancing

Freestyle dancing is always a fun option but if this is too intimidating for your students then guided dances are a great option. Go Noodle is a fun resource for and has a range of options. - Paired Yoga

Similar to the individual stretching or yoga poses, cards can also be made to allow students to stretch in pairs.

Key Takeaways

- Brain breaks are short, planned activities that allow the restoration of neurotransmitters and the engagement of different regions in the brain

- Physical movement, changing the type of mental activity, or simply moving to another part of the room can all serve as effective brain breaks

- Brain breaks can be used when you notice students are struggling to concentrate or becoming distracted

- Implement brain breaks before students become too distracted

- Create a repertoire of brain break activities based on your student’s strengths and interests

- Brain breaks can last between 5 and 10 minutes

- Introduce activities one at a time to ensure students can use them efficiently to reduce

transition times - Encourage students to self-regulate and learn to recognize how to take brain breaks independently